Early on in the Charles Bukowski compilation The Bell Tolls For No One, a narrator named Bukowski pulls his car over to the side of the road to stop and marvel at a hideous-looking farm animal. “When one ugly admires another,” he muses, “there is a transgression of sorts, a touching and exchanging of souls, if you will.” It could be said that much of Charles Bukowski’s writing is devoted to this moment when two imperfect forces collide – whether it’s drunken lovers helping each other endure a cold night or a downtrodden man recognizing a kindred spirit in the gnarled face of a hog. Bukowski’s work recognizes humanity’s myriad imperfections. (“Human relationships don’t work,” one of his protagonists flat-out states in a story titled “An Affair of Little Importance.”) And yet in his broken-down characters’ heartbreaking attempts to find solace in a world “half…run on hatred, the other half on fear,” there is a sly triumph, if only in their refusal to give up and drop dead.

Early on in the Charles Bukowski compilation The Bell Tolls For No One, a narrator named Bukowski pulls his car over to the side of the road to stop and marvel at a hideous-looking farm animal. “When one ugly admires another,” he muses, “there is a transgression of sorts, a touching and exchanging of souls, if you will.” It could be said that much of Charles Bukowski’s writing is devoted to this moment when two imperfect forces collide – whether it’s drunken lovers helping each other endure a cold night or a downtrodden man recognizing a kindred spirit in the gnarled face of a hog. Bukowski’s work recognizes humanity’s myriad imperfections. (“Human relationships don’t work,” one of his protagonists flat-out states in a story titled “An Affair of Little Importance.”) And yet in his broken-down characters’ heartbreaking attempts to find solace in a world “half…run on hatred, the other half on fear,” there is a sly triumph, if only in their refusal to give up and drop dead.

Since 2008, City Lights Books has been compiling the uncollected and unpublished works of Charles Bukowski in a series of volumes. The latest is The Bell Tolls For No One and draws the vast majority of its material from a series of short pieces Bukowski wrote, called “Notes of a Dirty Old Man,” which were serialized in publications such as NOLA Express and the L.A. Free Press from 1967 to 1976. Unsurprisingly, the collection is something of a grab bag; the stories are eclectic, with several pieces that read almost like speculative fiction. As always, Bukowski remains incendiary: one of the stand-out stories is a post-apocalyptic fever dream that details what might have happened if the notoriously pro-segregationist candidate George Wallace had become president (policies include a curfew for African-Americans and slating 85 percent of library books for destruction).

In more than one piece, Bukowski’s hardboiled detective-style narration reveals his love of vintage noir writers such as Mickey Spillane: “Jane was a natural, and she had delicious legs…and a face of powdered pain. And she knew me. She taught me more than the philosophy books of the ages.” Elsewhere, Bukowski spins a violent Western yarn in which he subverts the classic trope of the stranger who drifts into town, complete with poker-faced one-liners that wouldn’t be out of place in a Clint Eastwood movie: “If God created you, He was sure as hell in need of better instruction.”

Despite its wide-ranging nature, The Bell Tolls For No One is largely comprised of the bawdy sex tales many people think of when they hear the name “Charles Bukowski.” These are examples of the debauched fiction that some critics have labeled misogynistic, or at the very least sexist, and have perhaps prevented the literary establishment from ever fully embracing the author. The numerous stories of lovers bickering and reconciling amid a sea of alcohol and infidelity tend to blur together (particularly since the stories lack titles). And the fact that, at first glance, these pieces offer little in the way of traditional writerly finesse, and tend to wallow in the ugliest forms of human behavior, the stories can make for difficult reading at times.

Nonetheless, Bukowski’s work occasionally reveals – particularly as the book moves chronologically toward the late ‘70s – some hard-won truths, such as when the author describes a feuding man and wife: “There was an inflexible grimness to it all, and yet we had to pass through the grimness, we needed it, somehow, like we had once needed the love.” Bukowski’s characters pursue their worst interests: they take a horrible situation and compound it – out of stubbornness, pride, or self-destructive impulses. A narrator remarks: “It’s that way for people all over America. We do things without knowing why, and later we don’t care why we did them.” Their behavior isn’t pretty, but it is profoundly human.

The highpoint of the collection arrives late with “A Dirty Trick on God,” which follows the plight of hapless protagonist Harry Greb, an assembly line-worker whose lonely existence sees him drinking beer in the bath and whose roommate may or may not be conducting experiments on him. The actual plot of the story is sophomoric – bathtub flatulence plays a key role, for one thing – but the piece contains several haunting passages in which Bukowski depicts the world through his character’s downcast eyes. Bukowski expertly hones in on the quiet desperation of Harry’s life, such as in this scene when Harry stops at an unnamed chain restaurant for dinner:

“Harry looked around at the people. They all looked ugly and tired. They were ugly and tired. They were losers. Where were the winners? Where were the beautiful people? All these around him: it seemed to be a crime to be alive. And he was one of them.

“Harry sighed and looked down at his work-beaten hands. Hell, he was tired but it wasn’t a good tiredness. It was like he had been gypped. Well, he had plenty of company: a world-full.

“The waitress brought his plate. She slammed it down, smiled a horrible false smile, said ‘ENJOY!’ with a rasping voice, began to walk off.”

Few passages in The Bell Tolls For No One are as exquisitely rendered as this. Instead, they trade in the kind of raw, tossed-off style Bukowski became known for. For this reason and others, the collection may appeal the most to readers who already have an interest in Bukowski.

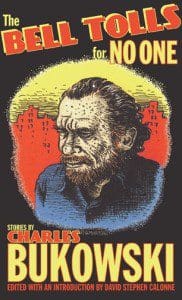

Yet like Robert Crumb, whose art appears on the cover of The Bell Tolls For No One, Charles Bukowski represents a kind of brazenly counterculture spirit that holds in contempt anything that represents the Establishment. Read in this light, this newest compilation can be viewed as more than the self-admitted “notes of a dirty old man,” but as the further works of an iconoclast who, much like the underground comics artists and punk rock bands of the late ‘70s, waged war against all that was supposedly “decent” and conventional for the sake of getting at the grit of human experience.