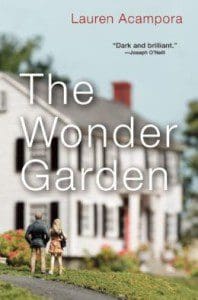

It takes a skilled writer to make us see the familiar as something new. In her first book of fiction, The Wonder Garden (Grove; 386 pages), Lauren Acampora turns an anthropologist’s discerning gaze on the everyday sights and sounds of suburbia. In doing so, she creates the impression these commonplace scenes and images are imbued with some hidden meaning, whether it be a foreign girl visiting for the first time a mall, where she “touches the clothing in Aeropostale as if it were powdered with gold dust,” or the markings on a “wooden coffee table that still bears the scars of children’s homework.”

It takes a skilled writer to make us see the familiar as something new. In her first book of fiction, The Wonder Garden (Grove; 386 pages), Lauren Acampora turns an anthropologist’s discerning gaze on the everyday sights and sounds of suburbia. In doing so, she creates the impression these commonplace scenes and images are imbued with some hidden meaning, whether it be a foreign girl visiting for the first time a mall, where she “touches the clothing in Aeropostale as if it were powdered with gold dust,” or the markings on a “wooden coffee table that still bears the scars of children’s homework.”

The Wonder Garden began as a novel until Acampora realized her story’s central protagonist was too passive of a character to carry the weight of hundreds of pages. Thankfully, she discovered that several of the novel’s supporting players possessed fascinating interior lives worth exploring. Acampora ultimately resurrected the project as a series of interwoven stories set around the affluent Connecticut community of Old Cranbury. These are characters who appear “stuck,” paralyzed by indecision while at the crossroads of middle-age, young adulthood, or new parenthood. The pleasure of reading The Wonder Garden comes not from watching these people escape the traps they may or may not have set for themselves, but in witnessing their struggle and seeing, despite the extreme wealth on display through the book, a mirror of our own lives.

Thanks to her writing’s suburban milieu, Acampora has already drawn comparisons to writers like John Cheever and Richard Yates, whose novel Revolutionary Road seems like a possible influence. Acampora has cited the work of Flannery O’Connor as a guiding force, though it might be said that these stories avoid the depths of shattering despair and violence which O’Connor mined so well. Instead, they seem to skew closer to the suburban “dramedy” of Tom Perrotta’s Little Children.

In the collection’s title story, we follow a clueless but well-meaning Christian housewife whose decision to welcome a foreign exchange student from Bangladesh into her home leads to unforeseen consequences; “Visa” explores the trials and tribulations of a single mother who must contend with the “Mommy Police” at her daughter’s school—even as she plans a move to Paris with her mysterious new lover; while in “Aether,” a community college student and budding actress ponders the fate of her recently separated parents while navigating the druggy haze of an outdoor musical festival. These stories rarely build to the explosive climaxes or sudden epiphanies one might expect to find in commercial fiction. Rather, Acampora offers up realistic vignettes of disappointment and disillusionment, their resolutions (or lack thereof) leaving the reader to contemplate the fate of these characters long after the last page has been turned.

Those hoping for an escape from the insular world of Old Cranbury may be left disappointed; considering how blissfully ignorant these characters are, they rarely give a thought to anyone outside of their privileged bubble. A late exception comes in “Elevations,” in which a man laments that his partner has the gall to plan a safari to Africa without giving a thought to the indigenous population who are exploited by the tourist trade. Critiques of these characters and their lifestyles are expressed through internal monologue—such as when a house inspector remarks that the homeowners he interacts with see themselves as the “uncontested, oblivious owners” of their surroundings, without “even the awareness to doubt this”—and in Acampora’s subtle tendency to compare the adults in the book to children. While some readers might be left wanting relief from the conspicuous consumption found here, it’s difficult to find fault with Acampora’s technique. Again and again, the prose delights on a purely sentence level, such as when she describes a skylight being a “black velvet kerchief crusted with stars,” or when an untouched salad is compared to a “careful little Eden.”

Like the best chroniclers of suburban dysfunction, from Cheever to her fellow Connecticut refugee Rick Moody, Lauren Acampora is clearly fascinated by human behavior in its myriad forms. Her eye never wavers when fixed on the neighbors next door, whose ethic is to above all “live among beauty” and yet still find themselves “bedeviled by a nagging melancholy.” With The Wonder Garden, Acampora has delivered a smartly written and satisfying collection of stories that reminds us once again why trying to keep up with the Joneses is a losing game.