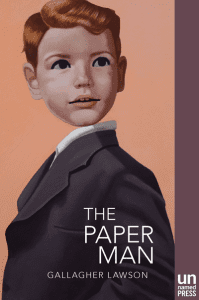

Gallagher Lawson’s first novel, The Paper Man (261 pages; Unnamed Press), opens with a scene you might expect in a coming-of-age tale: a sheltered young man has just arrived by bus to an unfamiliar city, eager and more than a little anxious to start the next chapter of his life. The difference here is that our protagonist, Michael, is a walking and talking paper mache’ construction. Given his unusual appearance, Michael is dreadfully concerned with fitting in his new surroundings. Fortunately for him, he might not be the strangest resident of the novel’s unnamed seaside province: his arrival in town is heralded by the appearance of a dead mermaid in the middle of the road. The sight proves an ill omen as Michael soon finds his belongings stolen by an eye-patch-wearing talk radio host and his paper form marred by a sudden rainstorm. Early in the novel, Michael reminds himself that “he was the stranger here,” and, given the existential horror prevalent in The Paper Man, one senses Gallagher Lawson would hardly be unpleased if this phrase brings Albert Camus to mind for his readers.

Gallagher Lawson’s first novel, The Paper Man (261 pages; Unnamed Press), opens with a scene you might expect in a coming-of-age tale: a sheltered young man has just arrived by bus to an unfamiliar city, eager and more than a little anxious to start the next chapter of his life. The difference here is that our protagonist, Michael, is a walking and talking paper mache’ construction. Given his unusual appearance, Michael is dreadfully concerned with fitting in his new surroundings. Fortunately for him, he might not be the strangest resident of the novel’s unnamed seaside province: his arrival in town is heralded by the appearance of a dead mermaid in the middle of the road. The sight proves an ill omen as Michael soon finds his belongings stolen by an eye-patch-wearing talk radio host and his paper form marred by a sudden rainstorm. Early in the novel, Michael reminds himself that “he was the stranger here,” and, given the existential horror prevalent in The Paper Man, one senses Gallagher Lawson would hardly be unpleased if this phrase brings Albert Camus to mind for his readers.

The plot of The Paper Man gains momentum when Michael encounters an eccentric artist named Doppelmann, who is fond of spouting Wildean aphorisms such as “People with style are becoming less and less appreciated,” as well as his childhood sweetheart Mischa, now a woman well-aware of her seductive hold over Michael. The three of them engage in a torrid love triangle even as violence and political unrest threaten to swallow up the city around them. Lawson utilizes this set-up, which somewhat recalls Gustav Flaubert’s classic novel Sentimental Education, to explore timeless issues such as the fluidity of identity and sexuality, the commoditization of art, and the struggle between the individual and society as a whole.

The novel proves a brisk read – Lawson favors a straightforward style and most chapters clock in around six pages. The prose comes most alive when Lawson allows the surreal quality of the urban environment to seep into the writing itself: “Nearby, fried food sizzled in steam and smoke that floated by in clouds shaped like ghosts of animals.” Nightmarish imagery like a woman giving birth to fish in the alley of a restaurant – fish that are then immediately carted off to customers by a harried waitstaff – and unexpected bursts of violence mean that fans of David Lynch and Franz Kafka will feel oddly at home in this askew world.

Given that The Paper Man‘s fantastical trappings veer into the realm of magical realism, it’s perhaps a disappointment that the novel never truly escapes the conventions of the coming-of-age story (an occasional fixation with male impotence seems similarly familiar). Nevertheless, Gallagher Lawson has delivered a promising first book and gives further proof that the journey into adulthood is rarely painless – especially when forgetting your umbrella at home might mean you’ll be turned to pulp.