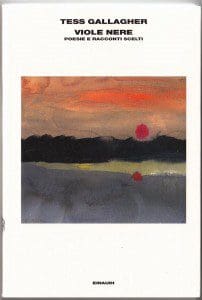

Riccardo Duranti is perhaps best known for being one of the select people in the world to have translated all of Raymond Carver’s work. (According to Duranti, there have only been two: he and Haruki Murakami). But his work includes translating more than one hundred titles by authors such as Richard Brautigan, Peter Orner, Elizabeth Bishop, Cormac McCarthy, Philip K. Dick, Tess Gallagher, Lou Reed, Sandra Cisneros, Ted Hughes, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Tibor Fischer, Michael Ondaatje, Isaac Bashevis Singer, and many more. Duranti is one of the most notable literary translators of English into Italian, and his career has its roots in the United States, where he met Tess Gallagher, who introduced him to Carver.

Translator, essayist, and poet, Duranti taught English Literature and Literary Translation at “La Sapienza” University in Rome. In 1996, he was awarded the National Prize for Translation, Italy’s most important translation prize. Recently, he decided to fulfill his dream of refurbishing his family’s old country farm located in the wild hills of Sabina just outside of Rome. Now living with his two dogs, Baldo and Nero, and eight cats, he spends his time sowing seeds into colorful flowers and fruit trees, turning organic olives into delicious oil, and translating powerful visions into graceful haikus. We spoke to him at his farm about his work.

ZYZZYVA: I know your farm means a lot to you. How does your home affect your creative work, as a translator and as a poet?

Riccardo Duranti: This place represents my roots because this house used to be my great-grandfather’s farm. It was abandoned around the Fifties. It had gone down to ruin until I bought it back from relatives–I razed it and built a new house with the same stones, the same bricks, on the same place.

Z: The original materials…

RD: Exactly. I moved here as soon as I retired from the University, and I’ve been living here for five and a half years now. It does affect my work because this is a very peaceful place and I feel at ease here–no interruptions, no noise…

Z: Except me bothering you with my questions…

RD: Oh, that’s a nice break from the loneliness!

On the creative side, there’s one book of poems that’s been written mostly here. And the farm recently became Coazinzola Press, a publishing house—let’s say a publishing farm-house—that publishes mostly poetry books. Also, here I translated about five books, in this house, since I moved here in 2008. The first one was Beginners by Raymond Carver.

Z: You said translation is an impossible activity from a theoretical point of view, but from the practical point of view, it is not only possible but also necessary. What do you mean? What is translation for you?

RD: It means that translation is a paradoxical activity–something that cannot be done and yet it is done. You are always in between with translation. You fall between the original text and the translation. You span the gap somehow. You have to do acrobatics in order not to disappear in the gap. That’s what translation is for me.

When I was a teenager I read one of Leonardo Da Vinci’s proverbs, which said, “If you can drink from the spring, you shouldn’t drink from the pitcher.” I agreed with that, and I applied it immediately to literature—if you can read the original, why should you bother yourself with the translation? But at the same time I also thought about those people who cannot drink at the spring; they need the pitcher. So, my effort has been to keep the water in the pitcher as clean, as fresh, as pure as possible, and produce an experience similar to drinking directly from the spring.

Z: Do you think translation is more like traversing a flooded river or more like sinking into a lake’s still water?

RD: It can be both. It depends on the energy of the text. I think that translation is not only a transfer of meaning, but also a transfer of energy. If the text is very dynamic, the translation is very dynamic—and it’s like a river with lots of currents and streams. One current drags you one way and a cross-current drags you the other way.

Z: Let’s talk about Raymond Carver. How did you become his translator?

Z: Let’s talk about Raymond Carver. How did you become his translator?

RD: I started translating him just before and right after his death. I was chosen by his wife–she though my translations were the most faithful to his voice. So, in 1998, when she was selling the Italian rights of Carver’s work, she put in the contract a clause that said it had to be translated by me.

Z: You tell of your first meeting with Carver in a vivid short story, “L’incontro.” How was your relationship with him?

RD: I met him almost by mistake. I knew him as the partner of Tess Gallagher, but I wasn’t aware he was the writer. She always called him just “Ray,” and I didn’t know that Ray was actually Raymond Carver. I found out when I met them in person. He asked my opinion on the first translation of a book of his, and I was taken completely by surprise. But afterward, after this weird beginning, we got along very well, and I think that was because we felt a kind of common background. We were people who were not supposed to be intellectuals, we were not supposed to be writers, because we came from families that didn’t have that kind of tradition. But we somehow made it, we made that jump. This circumstance created a strong feeling of fellowship.

Z: Something he had in common with Tess Gallagher, too.

RD: Yes. The three of us actually felt this fellowship. There was a great empathy. Unfortunately, it was very brief because I met them in 1985 and three years later Ray was gone. We had a lot of plans that never carried through. He wanted to take me fishing for salmon in the Northwest, but we never made that happen. The friendship lasted beyond that–with Tess. We still see each other, we write often and keep up with each other.

Z: You mentioned Carver’s death. In which way did this event affect your approach to the translation of his works?

RD: I translated only one short story before he died. It was his last story, Errand. During his visit here in Italy in 1987, he gave it to me to translate from the proofs of The New Yorker, because he wanted to publish it in a magazine of another common friend, Arsenale. The story is about Chekhov’s death. It is a wonderful story—besides being eerie in the fact that he describes Chekhov’s death and after a few months he found out about his lung cancer exactly in the same way Chekhov found out about his TB—this is the first story he doesn’t set in contemporary America, but in Russia and Germany at the beginning of 20th century. It could have been the first piece of a more cosmopolitan way of telling stories, a new creative path, but it was cut short by his disease and then by his death. Right after his death I received the first commission to translate Fires, and then, after that, his last six stories, and I began translating him in earnest. At first it was very difficult to translate because I was still mourning him. But soon, I found out that translating was a way of elaborating the loss. Translating was like getting that voice back, trying to recover the friendly voice I had lost.

Z: Let’s talk about Gordon Lish. I think, and I know it isn’t a popular idea, that some of the edited short stories are better than the original ones. I am keen to hear your opinion about that.

RD: This is my opinion: Gordon Lish was an excellent editor. He knew what to do and he had a good ear for improving short stories. The problem with What We Talk About When We Talk About Love is that he wanted to exaggerate. It was his chance to do something spectacular. I know that he first edited the short stories in a normal way, and there are letters that testify to Carver’s gratefulness about that work. But right after that, when Carver thought the process was over, Lish edited the stories a second time—actually he didn’t just edit them, but cut them to pieces.

My theory is that Lish wanted to push minimalism, this new way of writing, which was his way of writing. When you read Lish, the impression is like you took a handful of sand and rubbed it over your eyes. It hurts. But what made Carver’s writing powerful was the kind of humanity that was in it. Lish tried to cut out that humanity. Lish almost succeeded in this. He did impose this label “minimalism” on the literary world, but pretty soon Carver denied that he was one of them.

Z: I am curious about how the mind works during the translation process. Sometimes, you find a solution to a challenging passage during the night. You suddenly wake up with the answer you were looking for during an entire day! What do you think about the role of the unconscious mind in the process of translation? And what about your personal experience?

Z: I am curious about how the mind works during the translation process. Sometimes, you find a solution to a challenging passage during the night. You suddenly wake up with the answer you were looking for during an entire day! What do you think about the role of the unconscious mind in the process of translation? And what about your personal experience?

RD: Yeah, I think it’s mostly an unconscious process. It works on a subconscious level, so when you relax, the solution comes to you. I try to concentrate as much as possible on the voice that comes from the text, trying to imitate it somehow, because each text has a different outcome and different needs. Sometimes you’re more in tune with the voice, sometimes less. It’s interesting when I re-read some old translations I did, which is not very often. I am surprised by the fact that there are so many voices inside my translating voice–from tragic, to comic, to ironic, to poetic, to lyrical, and so on.

Z: Translating implies a lot of different skills. Not only having deep and detailed knowledge of two languages, but also the ability to write somehow, and having a background in many other different areas. You are a great expert, for example, of flowers, plants, and botany in general. But you could come across something you don’t know very well in a book you’re translating, like American football or Cajun music. What happens in such cases?

RD: You try and learn it, basically. At the beginning of my work, I had to find my own resources. I remember when I translated Cormac McCarthy’s All the Pretty Horses, I didn’t know anything about riding, so I had to learn all the technical jargon. Sometimes that’s not enough. With exotic plants’ names, for instance, even if you found the scientific name, you still have to come up with the popular name, for which there may be no equivalent in Italian. So you make that name up. And if it works, it works. It worked for Olive Schreiner. I remember there was a plant that only grew in the karoo, the South African desert. Unfortunately, there was no equivalent in Italian for “ice grass,” so I made up erbadiacciola. It worked well in the text, and that’s all I cared about. Now, it’s much easier to find information about things you don’t know with the Internet.

Z: You have translated a lot of poetry. What are the main differences between translating poetry and translating fiction?

RD: I actually prefer translating poetry. It’s more difficult, more concentrated. Poetry allows me to have a very short, but intense relationship with the text. Translating prose is like drinking wine. Poetry is more like grappa.