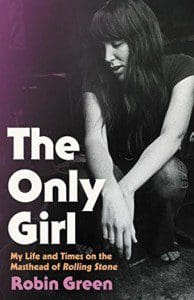

Journalist turned award-winning Sopranos screenwriter Robin Green adds a new credit to her illustrious career with the memoir, The Only Girl: My Life and Times on the Masthead of Rolling Stone (304 pages; Little, Brown and Company). In the book, she recalls how she became “paid, published, and praised” as a writer for the iconic music magazine Rolling Stone. Starting from her time studying English at Brown, where she was the editor of Brown’s literary journal and the Brown Daily Herald (and was the only girl to do so), Green hoped to land a job in the publishing industry. At 22, she moved to Manhattan and began secretarial work. During her lunch breaks in the city, she’d stare longingly at the suit-clad women who passed with briefcases in hand. In Green’s eyes, they had “glamorous and fulfilling jobs,” but in her heart she sensed that wasn’t the path for her, which induced self-loathing and disgust: “If I didn’t want that, then what the hell did I want?” She ultimately moved out to west to Berkeley and got hired at Rolling Stone, where she would develop her writer’s voice: “Showing a little of the arch and ironic tone.”

Journalist turned award-winning Sopranos screenwriter Robin Green adds a new credit to her illustrious career with the memoir, The Only Girl: My Life and Times on the Masthead of Rolling Stone (304 pages; Little, Brown and Company). In the book, she recalls how she became “paid, published, and praised” as a writer for the iconic music magazine Rolling Stone. Starting from her time studying English at Brown, where she was the editor of Brown’s literary journal and the Brown Daily Herald (and was the only girl to do so), Green hoped to land a job in the publishing industry. At 22, she moved to Manhattan and began secretarial work. During her lunch breaks in the city, she’d stare longingly at the suit-clad women who passed with briefcases in hand. In Green’s eyes, they had “glamorous and fulfilling jobs,” but in her heart she sensed that wasn’t the path for her, which induced self-loathing and disgust: “If I didn’t want that, then what the hell did I want?” She ultimately moved out to west to Berkeley and got hired at Rolling Stone, where she would develop her writer’s voice: “Showing a little of the arch and ironic tone.”

Green clearly still holds admiration for the people she worked with at Rolling Stone. In 1974, the magazine had a powerhouse editorial team, including women like Marianne Partridge as managing editor, Christine Doudna as her assistant copy-chief, and Sarah Lazin and Harriet Fier as fact-checkers — the “sisterhood had become powerful,” Green observes. Jon Landau (who eventually because Bruce Springsteen’s manager) credited them for improving his writing “by a factor of approximately fifty percent,” and Chris Hodenfield praised how they turned him “from a chaotic hog-slopper into something resembling a writer.” Green also fondly recalls several experiences with Hunter S. Thompson and heralds him for his writing. “Nobody was saying it better,” she states. She conveys the excitement she felt during the second night of the Rolling Stone editorial conference in Big Sur, when she was in the backseat of Thompson’s rented mustang with Annie Leibovitz riding shotgun. Thompson was making hairpin turns, driving with the headlights off on Route 1—and all of them were heavily intoxicated:

It occurred to me that I seemed not to care. I felt alive. Immortal. Lucky to be in the car, living on the literal edge. This, I realize, was the point of Hunter. He didn’t just write that stuff; he lived it. And if we went crashing down that cliff on the Pacific Ocean, so be it. What better way to die?

Green’s career in TV began with a phone call from John Falsey, who she knew from the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. Falsey was reminded of her talent after reading Green’s restaurant reviews in the LA Times. In 1986, Falsey and his playwright partner, Joshua Brand, created a show called A Year in the Life in the style of what became known as “prestige TV.” The show was a “subtle and realistic drama” similar to Hill Street Blues and its predecessors, and they wanted Green to write a script for it in two weeks. Although her first attempt failed to meet their standards, she was given a second chance. Green decided to take her own advice, harkening back to when she was a teaching fellow at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and advised her students: “Copy a master. You probably won’t come close but you might at least have something that works.” Green found inspiration in John Updike, citing him as “an astute observer of suburban subtext,” and succeeded in her shot at re-writing the script.

Like many writers, Green also greatly admires Joan Didion and, as it turns out, the admiration goes both ways. In fact, Green once wrote a profile on Dennis Hopper for Rolling Stone that Didion enjoyed so much, she asked a friend to phone Green and let her know. Coincidentally, Green’s professional relationship with her husband, Mitch Burgess, is not unlike that of Joan Didion and her late husband, John Gregory Dunne. As Didion discusses in her memoir The Year of Magical Thinking, she and her husband were known to edit each other’s work intensively, so much so that it was often difficult to tell who contributed what. In Green’s case, she confessed to Jeffrey Brand that she had been “giving Mitch’s ideas as her own.” Subsequently, Brand brought Mitch on as a story-editor and minted Mitch and Green as a creative duo through a shared writing credit. This turned out to be a lucrative career for the pair, leading to several Emmys, Golden Globes, and Peabody’s for their work in shows such as Northern Exposure, The Sopranos, and their own creation, Blue Bloods.

Yet for all of Green’s numerous accolades, The Only Girl’s vigor comes from her blunt acknowledgment of the diffidence she faced early in her career. To follow her path to being paid, published, and praised amid many tribulations proves both a solace and great reward.