“The past is never dead,’’ as Faulkner memorably put it. “It’s not even past.’’

“The past is never dead,’’ as Faulkner memorably put it. “It’s not even past.’’

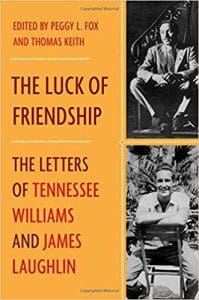

But the mutability of literary fashion continues to be regrettable. A new collection, The Luck of Friendship—The Letters of Tennessee Willams and James Laughlin (392 pages; Norton), reminds us of the importance of respecting the Muse (regardless of reviews), the seeming bygone virtues of literary mentorship, and the need to cast aside judgement to make way for love. Tactfully edited by Peggy Fox and Thomas Keith, Laughlin’s longtime associates at New Directions, the avant-garde publishing house he founded, it presents a little-seen side of the playwright.

Too often portrayed retrospectively as a pill-popping, promiscuous caricature, a kind of Capote with theatrical wings, this record shows him as a devoted, if sometimes anxious friend, seeking and getting the approval of Laughlin—an accomplished poet in his own right, who was an advocate for Williams’s early works, from The Glass Menagerie to A Streetcar Named Desire. (They were also avid collaborators on everything from typeface to cover design; a subject Williams was intensely interested in.)

“I have done a lot of work, finished two long plays,’’ he writes in 1947, from New Orleans. “One of them, ‘A Streetcar Called Desire’ turned out quite well. It is a strong play…but is not what critics call ‘pleasant.’ In fact, it is pretty unpleasant. But we already have a producer ‘in the bag.’ A lady named Irene Selznick [estranged wife of David Selznick and a daughter of Louis B. Mayer]. Her chief apparent advantage is that she seems to have millions.’’

Laughlin, as always, was supportive. Even when he had reservations, or suggestions about Williams’s work, he phrased them encouragingly, and was an advocate for controversial material like his 1948 story collection, One Arm and Other Stories, which depicted gay life explicitly, and tirelessly urged Tennessee to continue work on his underrated poetry.

Perhaps the secret to the longevity of this alliance was in the physical distance between the two men.

“Their joint story, while admittedly only a small part of the life of either man, provides a window into the literary history of the mid-twentieth century and reveals not only the self-destructive tendencies of a great artist, but also his lifelong perseverance to remain both a poet and an experimental playwright, supported in his endeavors by the publisher he considered his his one true friend,’’ Fox writes in the introduction.

True to form, Laughlin backed Williams in his later efforts, even when they were viciously attacked. It’s a commonplace (seen also in Rebecca Miller’s recent documentary about her father, Arthur) that after enjoying early success of incredible magnitude, the artist must be knocked down a peg or ten by critics for his subsequent work, even though they obviously stem from the same sensibility. The light may burn brightest in youth, but the Victorian maidens of the press can’t resist the temptation to engage in schadenfreude at the inevitable fall.

“Dear Tenn,’’ Laughlin writes in 1953. “I’m glad that you have been encouraged by lots of letters from people who liked Camino [Real]. They are right and the dopes are wrong. But it all takes time. You must be patient. The world catches up with good things slowly. You’ve just got to develop a thick hide. I went through all of this with New Directions. For years almost all of the reviews of all the books were ridicule and scorn. You just have to sit tight and pay no attention and believe in yourself.’’

The publisher’s modesty, too, belied his talent. I was lucky enough to interview Laughlin some years back, and he recounted how he founded New Directions at Ezra Pound’s behest. He’d interrupted his studies at Harvard to sit at the cantankerous poet’s feet in Rapallo.

“When I first went there, I was trying to write, and I would show him things,’’ he recounted wryly. “He’d always tear them to pieces: too many words, too ‘poetic.’

“He finally said, ‘You’d better go home and do something useful.’ I said, ‘What is useful?’ and he said, ‘If you have the guts, you might murder Henry Seidel Canby.’ Henry Canby was the editor of the Saturday Review, who was very old-fashion, and always getting after Ezra.’’

“We decided that wouldn’t be very practical, so he said, ‘Well, you can become a publisher’ – and gave me letters to William Carlos Williams and his other literary friends.’’

Despite Pound’s protestations, Laughlin, who died in 1997, was a serious, if underappreciated, poet in his own right. I’d be remiss not to recommend, along with the Williams correspondence, his Collected Poems (New Directions, 1,214 pages), a massive volume full of unexpected pleasures, like this:

The Poet To His Reader

These poems are not I

hope what anyone ex-

pects and yet reader

I hope that when you

read them you will say

I’ve felt that too but

it was such a natural

thing it was too plain

to see until you saw

it for me in your poem.

Williams’ heroine Blanche DuBois famously declared she’d always depended on the kindness of strangers. But in Laughlin, he found an initial stranger who became a stalwart friend. Every writer should be so lucky.

Wonderful and heartfelt ❤️