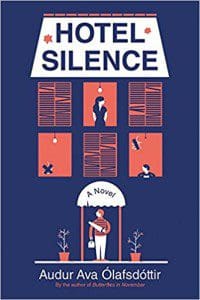

Icelandic novelist, playwright, and poet Audur Ava Olafsdóttir offers a bizarrely lighthearted and humorous—yet nonetheless moving—portrayal of suicide and post-war life in her latest novel, Hotel Silence (214 pages; Grove Press; translated by Brian FitzGibbon).

Icelandic novelist, playwright, and poet Audur Ava Olafsdóttir offers a bizarrely lighthearted and humorous—yet nonetheless moving—portrayal of suicide and post-war life in her latest novel, Hotel Silence (214 pages; Grove Press; translated by Brian FitzGibbon).

After a painful divorce and the discovery that his daughter is not his biological child, the middle-aged narrator, Jonas, determines to commit suicide. His next-door neighbor, a man preoccupied with issues of gender inequality and female suffering, unquestioningly lends him a rifle. But once Jonas realizes his daughter would likely be the one to discover his lifeless body, he instead buys a one-way ticket to a foreign country where he can complete the task alone. He packs minimally: “I pack for a corpse,” he declares, only bringing a few items, including his old diaries and his tool kit (in case the room has something that needs fixing or he needs to screw in a hook from which to hang himself).

Jonas travels to an unnamed city in an unnamed country, one recently destroyed by a similarly unnamed war, to stay at Hotel Silence. He is one of three guests, which both his taxi driver and the hotel’s owners, a young brother and sister, note is the most business the place has received since the end of hostilities. In fact, they hope that Jonas’s trip will mark an economic turning point for the city.

The citizens of this place can use the change in fortune. They have lost their homes, have been maimed, and have witnessed families torn apart. Jonas’s pain is entirely unlike what these people have faced, but Jonas’s mother makes a Tolstoy-esque point: “All suffering is unique and different…and therefore it can’t be compared. Happiness, on the other hand, is similar.” In other words, suffering cannot be quantified or ranked, but perhaps it can be approached in similar ways.

While at Hotel Silence, Jonas spends time reading his journals, which are largely fixated on the books he’s read and his past relationships with women. In one entry he writes: “Thanks for life, mom. Why not Dad? I thank Mom for giving birth to me and girls for sleeping with me. I’m a man who expresses gratitude.” While this sentiment may sound egotistical, Jones proves earnest. He is a man who is happy to help women, who appreciates the presence of women and the act of being of service to them. His interest in women seems to offer a welcome distraction from painful self-reflection: “How did I become me?” he thinks at one point, indicating a desire to achieve insight and to understand his failure to do so. Yet it is precisely this interest that ultimately convinces Jonas to give life a second chance.

He begins by doing small things around the hotel: he fixes closet doors and clears the sand out of showerheads. He later moves on to larger projects, like helping to build a home for a group of women in town so they can rebuild their lives. He assists the hotel’s owners (the sister happens to be a single mother) piece together a mosaic of nude women. The mosaic, of course, will never return to its original state, will always reveal the scars of its devastation. But like Jonas and the inhabitants of this war-ravaged city, much of its original beauty can be restored—and as Olafsdóttir shows in her winning novel, it is a task worth attempting.