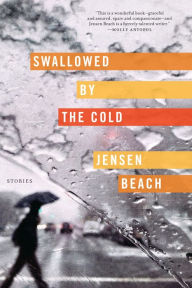

The stories in Jensen Beach’s second story collection, Swallowed by the Cold (208 pages; Graywolf Press), demonstrate again and again that self-destruction doesn’t happen in a vacuum. In “Kino,” we meet a young man named Oskar who swears he intended to torch just his own boat, but who ended up setting fire to an entire marina. Oskar happens to work at what seems to be a gay brothel called Kino Club, which an uptight man named Martin frequents. The two encounter each other at a party where Martin’s wife, Louise, gets too drunk. Suffering under the weight of Martin’s self-denial, she’s an alcoholic. It’s a quieter kind of tragedy, but at least as soul-rattling as, say, a car crash that leads to a coma (as in the story “Henrik Needed Help”). By the end of “Kino,” Martin abandons Louise on the side of the road to spend the night with Oskar.

These linked stories, set in Sweden, swivel among troubled lives. If it’s not alcoholism and infidelity, it’s a death in the family, the loss of a limb, a sinking ship, even war. All of this sorrow is thrown against rather prim backdrops: summer homes on the Baltic, apartments in “safe” neighborhoods, a fancy party at a Stockholm museum. Mix in the drama of Scandinavian weather and these settings make for fertile ground for Beach’s tales.

In an interview with him about his book, Beach told me he sought to accomplish what John Cheever did in “The Swimmer”: “It’s just all pain. The entire story is one of pain. And we’re never told the nature of it, or its reasons. Instead, we’re simply emerged in it, experientially.” Beach has accomplished what he set out to do. Swallowed by the Cold covers you in its web of anguish, but you won’t want to thrash yourself free, and you wouldn’t be able to anyway.

ZYZZYVA: I want to start with the question on which interviews often end: What’s next for Jensen Beach? Your first book was a collection of shorter stories. This last one is a collection of longer stories with recurring characters. Are you inching toward a novel?

Jensen Beach: I am indeed inching toward a novel. Inching might even imply a speed which is not yet there. The novel interests me as a form lately for similar reasons that I wrote Swallowed by the Cold, actually. I’m interested in the ways in which a book with a considerable dramatic scope can allow that drama to be explored in its intersections and connections, through coincidence and overlap. Swallowed by the Cold is a book of linked stories; and I find myself very interested in the challenge of that puzzle for this next project, too. So much so that I’m finding a similar motivating energy in writing this novel. At this stage of that manuscript, I’m just producing text. I couldn’t tell you yet what it’s about really. But I am excited by the challenge of holding an even larger number of parts up and seeing how they puzzle together.

Z: Many of these stories appeared in various publications. I’m trying to imagine how they read on their own. In “The Apartment,” which was published in the New Yorker. (The story, which is set in a Stockholm apartment complex, follows Louise, of “Kino,” getting drunk alone in her and Martin’s apartment, and then introducing herself to a new neighbor who she thinks is her dead ex-lover’s daughter.) There’s a moment near the end where Louise, referring (I think) to something that happens in “Kino,” says to her husband, “‘You should have stayed, Martin. You could have stayed. It wasn’t difficult.’” How do you think not knowing that reference affects the reader’s understanding of the story? What’s lost? Is anything gained?

JB: That’s a good read of the stories. I appreciate it. I’m always a little suspicious of writers who say too much about intention in their work, but here I go anyway. You’re totally correct to read this story in the context of “Kino,” and that line in particular, especially given the ending of that story. But I actually think of what Louise says in “The Apartment” as referring to Martin having left his babysitting duties for the neighbor boy, something that occurs earlier in the story. “Kino” was in mind when I wrote “The Apartment,” and I wanted something of “Kino” to rub off on a reading of “The Apartment.” I think that both instances speak to Martin’s dishonesty, his inability to keep his word, but also, in some ways, his sense of pride and appearances. This condition is, I think, part of what makes Louise so unhappy. At the same time I did want each story to stand on its own, so it was a balance I had to strike that would allow a reader of one individual story to see the drama of that story clearly but also allow a reader who’d seen all of the stories to hold on to something of the events in related stories.

Last week I gave this talk at the Juniper Institute, a summer festival at UMass Amherst—it’s a terrific week, forgive the plug. My students and I talked about “The Swimmer,” which might be one of my favorite stories. It’s just so insane and heartbreaking and kind of perfect. One of the conclusions we came to regarding the story was about the way Cheever lets the pain beneath the story’s surface take over about midway through. That is, the main character, Neddy Merrill, is exhausted from swimming the eight miles to his house; he keeps running into people he has harmed or who have harmed him in some way; he runs across an old friend who has had some medical issues—there are these amazing scars; he sees an ex-lover, there’s a flashback to her crying when he breaks things off with her; there are hints that something has happened to his wife, his daughters, his house, his fortune. This is an enormously reductive summary of the story, of course. The point is, the story is pain. The pain belongs at once to Neddy, to the other characters, to the setting, the weather, the way time is rendered. It’s just all pain. The entire story is one of pain. And we’re never told the nature of it, or its reasons. Instead, we’re simply emerged in it, experientially.

If you’ll forgive the comparison, I think I was aiming for something similar in the ways the stories in Swallowed by the Cold interconnect. Louise is talking about the night of the babysitting. She’s also talking about the night that “Kino” takes place. She’s also talking about the entirety of her relationship with Martin, which is fundamentally one of loss and regret and self-deception. So I guess I wanted the line to speak to each of those facts clearly, but also to the subterranean stuff in the stories—the pain of “The Swimmer”—that’s hard to name, define, but is very obviously there nonetheless.

Z: In Swallowed by the Cold, there’s a lot of weather. It’s never used as a cheap literary device; instead, it’s a fact of life, “neither a sign of things to come, nor the result of the past,” to quote your character Lennart in “Ships of Stockholm.” Sometimes, it helps drive the plot, like the storm in “The Drowned Girl,” which forces the interaction between Fredrik and Ingrid. I wasn’t tempted to just read weather as metaphor, probably because I knew these stories were better than that. Still, I could imagine a writer might be hesitant to use weather in fiction. (Donald Barthelme strictly forbade his students from using it in their stories.) Did you ever feel like you were writing against the pressure of melodrama? If so, was it a generative kind of pressure?

JB: You know to be perfectly honest with you, I don’t know that I thought about it too much in terms of something I should be careful with. I probably had a teacher at some point warn me against using weather as a literary device, and I’m sure my first thought was, “Watch me.” But I don’t recall whether or not that was a motivation in these stories. Weather is an important part of the Swedish landscape and the discussion of weather is something, at least to my friends and family, that seems culturally significant. In part, I think I just wanted to get that right. It’s dramatic—snow, rain storms, late night sunlight, early afternoon darkness, all of it. My father-in-law has a little summer cottage on the Baltic coast. He’s obsessed with weather. I love it. He’s got one of these electronic weather stations at the house—pressure, wind speed, temperature, etc.—and will often check it and then comment on the weather. The device is mounted on the wall directly across from an enormous window that looks out over the sea. I used to like to tease him that he could just look outside and see what the weather was doing. But, you know, I think I’ve come around to his way of thinking about it. Weather is fascinating. We want it so badly to hold meaning, to inform patterns, and predict mood and event. But of course it can’t really do any of those things. It just is. It doesn’t have any meaning, as much as it might seem to suggest that it does.

JB: You know to be perfectly honest with you, I don’t know that I thought about it too much in terms of something I should be careful with. I probably had a teacher at some point warn me against using weather as a literary device, and I’m sure my first thought was, “Watch me.” But I don’t recall whether or not that was a motivation in these stories. Weather is an important part of the Swedish landscape and the discussion of weather is something, at least to my friends and family, that seems culturally significant. In part, I think I just wanted to get that right. It’s dramatic—snow, rain storms, late night sunlight, early afternoon darkness, all of it. My father-in-law has a little summer cottage on the Baltic coast. He’s obsessed with weather. I love it. He’s got one of these electronic weather stations at the house—pressure, wind speed, temperature, etc.—and will often check it and then comment on the weather. The device is mounted on the wall directly across from an enormous window that looks out over the sea. I used to like to tease him that he could just look outside and see what the weather was doing. But, you know, I think I’ve come around to his way of thinking about it. Weather is fascinating. We want it so badly to hold meaning, to inform patterns, and predict mood and event. But of course it can’t really do any of those things. It just is. It doesn’t have any meaning, as much as it might seem to suggest that it does.

I grew up in California. For most of the year, we don’t have weather. Living in Sweden was my first real experience with seasons and the drama of storms. Now I live in Vermont, another place where weather is sort of central to the way life is experienced day-to-day. I like the ways that weather is a part of life. Something you at once spend a lot of time thinking about and planning for, and have to be adaptive to, but absolutely have no control over.

I’m drawn to stories that push past using cheap literary devices, flirt with them a little bit. In fact, I think there are some other moments in these stories—heavy drinking, affairs, a coma!—that push against such literary devices in similar ways.

Z: Some of the characters in this book are interested in inhabiting other people’s perspectives—something you do as a fiction writer. Louise in “The Apartment” muses that, “our individual memories of a shared event mean such different things to each of us. It had something to do with identity, she supposed, but she didn’t feel like chasing after the thought any further.” Out of context, this desire might seem empathetic, but in these characters’ cases it suggests something like self-concern, though maybe that reading is harsh or cynical. Could you chase after this a little further?

JB: Self-concern is a good way to put it, maybe a little gentle and forgiving. I think this impulse is also selfish, or maybe to be less judgmental about it, desperate. In Louise’s case, I think her unhappiness is mainly from Martin’s dishonesty with who he is and what he wants out of life. Of course these same shortcomings are true of Louise herself. I think that the thing that makes a character like Martin or Louise compelling is the ways in which they’re seeing, variously, that they do not even know themselves, and cannot know the interior lives of another person. For these characters, there’s something so sad about the fact that they’re only themselves, that they cannot know, let alone control, the impulses of other people. And maybe those of us who write fiction share this frustration.

Z: I’m trying not to be adulatory, but the “Winter War” stories are gems of ekphrasis. What gave you the idea to use the movie?

JB: Thanks so much! I like these stories a lot and haven’t had much occasion to discuss them yet. Parts of the book deal with Swedish history, particularly military history. In part this was simply because history interests me. In earlier drafts of the book, these threads were given more emphasis. I’m interested in engaging historical event in fiction. Investigating effect, consequence, even at great temporal distances. I wonder if that represents a similar relationship between creation and response that ekphrastic work does, but using history rather than art. That’s seeming like a sloppier connection than I wanted to make. I guess I’m trying to draw a similarity between art as object that literature can respond to and history as object that literature can respond to. When I was first thinking about this story in revision, I was thinking about parallel, and the film seemed a good way to explore it.

The choice to use this film was inadvertent in the beginning. I once went to an art exhibit at Moderna Museet (the museum of contemporary art in Stockholm) on surrealism. There was a ton of weird stuff going on—sushi being served off a woman’s naked body, people in odd costumes, a strange staging of a Brecht musical. It was weird, but fun. In a very early draft of the “Winter War” stories, it was a single story and it tried to capture that night. The problem was there wasn’t much of a story. It was just: character goes to an art exhibit at which strange shit happens. Boring and lacking drama. But as the military history started to become more prominent in the book, I wanted a way to explore that some more. The film seemed like a good way to capture the absurdity of bad art (the film is really terrible—I mean, equating an actual war with waiting out a winter at a summer cottage!) and also allow Bent’s experiences to be described without directly writing a story about his time in the war, which I think would have been hard, given his limitations in terms of his own recall and perception. There is also, and I’m not sure I want to admit this but will, some references in the story to myself and to the project of the book, generally. The mattress commercial at the beginning of “Winter War” One is for Jensen mattresses (a real company, but chosen only because it shares my name). And Bent and Rolf and Lennart’s family name is Strand, which is Swedish for Beach. These stories, in certain ways, critique my own approaches here. This book, any book, is an enormously personal project, right? I mean, there’s the heady stuff one can say about art—I made this to contribute to the larger conversation; this is a cultural artifact; I’m offering some central truth to the human condition, check it out; and so on. And I suppose those things are all true. But I also made this thing, selfishly perhaps, to look at it all and wonder: what’s this look like if I can somehow manipulate the ways in which this life can be perceived? Like the video artist has made a film that speeds up time so that he can experience a year, compressed, at his summer cottage, I’ve made a thing that allows me to look, by means of compression and attention and assumption and guesswork, at these people I like a whole lot, that is to say, Swedish people. Anyway, the whole thing, or that part of it, seems sort of comically fraught with all sorts of potential problems, so I just sort of decided to shrug and make some jokes about it and chuckle to myself and not worry.

Z: How did you arrive at the title of the collection? What are other titles were in the running?

JB: The book went through a couple different titles. I’ll save the boring details (he says before giving, after all, the boring details), but when I wrote the first draft of this book, the version that was my MFA thesis, I was listening to a lot of Ebba Grön, this Swedish punk band from the ‘70s and ‘80s. One of their songs has this chorus that’s something like, in translation, “I don’t have to be there/ I don’t have to be there.” It’s about not going to a club, about the suburbs, about acceptance and exclusion. Like a lot of punk music is both really personal and really political. It’s also kind of sad in tone and tenor. In response, I was calling the book before it was even more than just a couple stories Don’t Go, which is not a good title. It’s a line Rolf says in the first story right before he dies. And I sensed even early on that some of the thematic concerns here would be loss, absence, etc. Then it was called The Winter War, but I didn’t really want to put too much emphasis on one story, or in this case two. Swallowed by the Cold is a line from a Tomas Tranströmer poem called “After a Death,” which is also about loss, and about authenticity, and naming and defining things, and simulation, and about the wake, or after-effects of death. The line is actually: “They resemble pages torn from old telephone directories. / Names swallowed by the cold.” It’s a really heartbreaking and gorgeous poem.