In 1983, with a Guggenheim fellowship and his acclaimed novel A Boy’s Own Story in tow, Edmund White left what he calls New York’s “gay ghetto” and moved to Paris. The site of what White thought would be a jaunting continental vacation, a respite from the AIDS outbreak and the long shadow cast upon the utopian project of sexual liberation, Paris served as his home until 1998 and ushered in a renaissance for one of the progenitors of the gay novel.

In 1983, with a Guggenheim fellowship and his acclaimed novel A Boy’s Own Story in tow, Edmund White left what he calls New York’s “gay ghetto” and moved to Paris. The site of what White thought would be a jaunting continental vacation, a respite from the AIDS outbreak and the long shadow cast upon the utopian project of sexual liberation, Paris served as his home until 1998 and ushered in a renaissance for one of the progenitors of the gay novel.

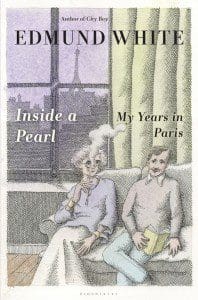

In his new memoir, Inside a Pearl: My Years in Paris (Bloomsbury, 261), White recounts these fifteen years abroad in loosely strung vignettes that read like feuilleton, a vortex of societal gossip tinctured with White’s erudition and humor and dotted with anecdotes on an inexhaustible parade of celebrities: Alain Robbe-Grillet, Emmanuel Carrère, Alan Hollinghurst, Michel Foucault, Susan Sontag, Harry Matthews, Yves Saint Laurent, Azzedine Alaïa, Paloma Picasso and far-away glimpses of the Rothschilds. If this list sounds both fascinating and exhausting, it is because White’s social life is both of these things. Yet Inside a Pearl is underpinned by the morose awareness that death haunts each page. In the midst of the allure and maddening craze of it all, of the glint of celebrity, the lunches at La Tour d’Argent, Le Grand Véfour, Le Voltaire and Lapérouse, the holidays spent at Gstaad, the fantasy and ornate pretention of an expat flaneur in Paris, White’s frank portraiture of friends and lovers who have died from AIDS-related complications revolves at the center as larger concerns with gay identity are filtered through existential crisis.

The book begins with White’s first few months in Paris, which are marked by dizzying disorientation. As he speaks little French, he comically finds companionship with schoolchildren and older women, two groups that speak more slowly than the intimates at the dinner parties of his French literary champion and friend, Marie-Claude de Brunhoff. In a comedic account of an interview with Eric Rohmer, White describes how he is left to vocalize questions he had rehearsed but has little to no idea what Rohmer is saying. White responds to the cultural and linguistic alienation with the fervor of a 19th century orientalist, gorging himself on French books bought from the bouquinistes that line the Seine, dissecting the distinction between French and American cultural life, and donning the scents and haute-culture of his new European identity. With amazing plasticity and a yearning to close the gap between him and his friends, White reshapes himself into a commander of the French order of arts and letters.

Yet a more acute alienation pervades the book as White attempts to convey the tragedy of his situation: marginalized, HIV positive in 1985, watching his friends and lovers die, trying to still find meaning in life, all the while seemingly screaming in a bell jar. This type of quiet tragedy finds beautiful expression when White and his lover come across a roadside accident in the still air of the French countryside:

“One night Hubert and I, as we drove home from the hotel, saw a car that had gone off the road into the ditch. We hopped out and peered into the driver’s side, where a young woman was slumped over the wheel, her ear running with blood. The headlights blazed into the tall, uneven grass. A little dog was yapping soundlessly in the backseat behind a closed window. The only noise was the creaking and ticking of the still-warm automobile. […]

“The entire family, even the grandmother, wanted to know whom it was before they would bother to call the ambulance. It was raining slightly as we all trudged down to the still-illuminated car in the ditch. If I’d been able to communicate with them more readily, I might have reminded them their hesitation could very well end up being partly responsible for the woman’s death.”

White has long been interested in how the autobiographical form allows him to explore identity politics and, more intimately, the ways a single individual constructs identity. To take a cue from his biographical portraits of Genet, Proust, and Rimbaud is to note that White’s literary project is interested in vitiating the fixed boundary between authorial and social persona. In writing for The New York Review of Books, White notes that Proust, with his New Critical leanings, separated the “Moi Social” (the person one meets at dinner parties) from the “Moi Profond” (the person who expresses himself only in writing books). By collapsing one identity into the other, White is able to preserve the ephemeral impressionistic feel of a dinner party, peopled by anonymous faces—the same anonymity that White prizes in an anonymous erotic relation which “allows free rein to any fantasy whatsoever”—and the authorial voice as completely alone, alone unto death, and, despite the ecstatic rapture of the erotic, ultimately separate again.

In Paris, White hoped to return to a life of normalcy. It was as if by wearing Bois du Portugal, he could change his identity and escape the horrors befalling gay men in New York. And Paris provided. White basked in a life luxury, new friends and lovers, and a vibrant intellectual life. Yet loss is never far away. The horror of AIDS for White is not so much the finality of death but that it categorically changed the basis of life as a way of being with others, that it curtailed the infinity of existence. On the night he learns he is HIV positive, White was “in anguish and couldn’t sleep, not because [he] was afraid of dying but because [he] knew [his] wonderful adult romance […] was doomed.” One of the more beautiful and poignant sentiments comes when White turns his attention to his friendship with Foucault. White writes, “Toward the end of his life Foucault thought the basis of morality after the death of God might be the ancient Greek aspiration to leave your life as a beautiful, burnished artifact.” As White reconstructs his memories of his years in Paris, eulogizing his long dead friends, he picks through both theirs lives and his to craft something of a series of glistening, beautiful artifacts.