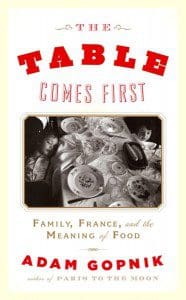

Where the famously poised, self-effacing, witty New Yorker critic proves to also be an ebullient, passionate, fiery man who admits to being in rage as much as in love with contemporary culture. As we sit down to talk about his latest book, The Table Comes First: Family, France, and the Meaning of Food (Knopf, 320 pages), he reflects on his debut as a writer and what lays ahead of him: to write a Big Book of Life and maybe try, one day, a different voice.

A prolific writer, Adam Gopnik has left almost no topic untouched, from Darwin and Lincoln to—not necessarily in that order – Mark Twain, Marx (Groucho), W.H. Auden, James Taylor, leaving New York for Paris, leaving Paris for New York, dogs, razors, artificial intelligence, libraries, Babar, snowflakes, fireflies, shopping, museums, magicians, 9/11, the DSK scandal (on which — no one is perfect — he quotes approvingly Bernard-Henry Levy), the Dreyffus Affair, television for plants, and, yes, even Jesus (more than once).

Not to mention his relentless blogging on the Jets, baseball and Canadian hockey, on which he posts sometimes twice a day.

And all that is just for his stint at the New Yorker: he also has under his belt a half dozen books of essays, two children books, a museum catalog; edited two anthologies and penned countless introductions to the works of photographers (Helen Levitt, Peter Turnley), contemporary artists (Wayne Thiebaud, Richard Avedon) and most of the big names in French literature (Hugo, Maupassant, Balzac, Proust). So: what’s an interviewer left to talk about that Gopnik has not already written about?

As we sat down for rooibos tea and pastries at the sundeck of a coffee house in the nondescript post-industrial zone around Bryant Street and Mariposa, I racked my brain and decided to use my old tricks: talk about dead people (French ones de préférence). American intellectuals love nothing more than the deep past: where the French shiver with post-traumatic stress flashbacks of high school indoctrination on the classics, New Yorkers revel in engaging with the great minds of the Renaissance.

After apologizing for the spotless blue sky and the dry, hot summer weather of this first day of November (Gopnik is a winter man), I mentioned I was teaching Montaigne. And off we went into a discussion of the essay form…

Adam Gopnik: Montaigne is like a god for me. He was one of the greatest revelations in my life…

ZYZZYVA: When was that?

AG: It’s a weird story. I was reading this completely forgotten American playwright, S.N. Behrman. His diaries were serialized in the New Yorker when I was a teenager in 1972 or 1973, and his ambition in life was to write a play about Montaigne. And I thought, “Oh, that’s interesting: that’s a writer I don’t know.” So I mentioned it to my dad, and he gave me, what was the name of the Elizabethan translator? … Florio! My dad is a… [pause for comic effect] snob, and said, “You should read the Florio edition because this is the translation that Shakespeare read.”

So that was the book I read. It had a huge effect on me. You know when you’re that age, 16 or 17, you can sort of read anything? You’re very much a sponge and some things that are in a way too difficult for me now I could read with a much more opened mind then. I could read through all the big Dickens novels like Bleak House. Nowadays you give me Little Dorrit to read, and I have to work my way through it. But in those days I would stay at night turning pages. Anyway, so I read Montaigne…

Z: And you liked the style?

AG: Loved it, I loved it! I loved the style, I loved the license it gave you. Here was something that was great literature that was both ambivalent and intimate; something that was not about big subjects but about small subjects. Having mixed emotions was the theme of it. I found that thrilling.

Z: As I was reading The Table Comes First, I thought in a weird way this was maybe the most personal of your books. It is a history of taste, of how and what and where we eat and why it matters. But it is character-driven and you are the central character guiding us. It is throughout very passionate.

AG: I’ve never said this, but the truth is every book is an object and a subject. The object of this book is food, but the subject really is my relationship with my mother. Because my mother represented food for me: she was cooking and she taught me how to cook. I hope this is not going to sound too terribly pretentious, but it’s about coming to terms with the femininity that I see in myself in that way.

Z: You do mention in the book “feeling a bit unmanned… by the practice of writing down recipes.” What does it mean to be a man who cooks?

AG: Exactly. I don’t drive, I don’t do a lot of things that men do, but I cook all the time. So I’m aware that, to use the Freudian word, I have “interjected” my mother to a great degree. And so this book is in part about that – obviously it’s also about a million other things!

Z: Coming back to Montaigne, there is a very Montaignian way in which the book is consubstantial to its author: whatever the topic, the reader thinks through the eyes of the author, and this is how you get this richness of texture and vision.

AG: The author is the worst judge of his own work. My editor at the New Yorker, Henry Finder, a brilliant editor, always teases me that my personal essays are often the least revealing about who I am and the impersonal ones are the most revealing. And what he means by that, I think, is that when I write about John Stuart Mill or Charles Darwin, I always recast them in my own image. So John Stuart Mill, when I write about him—I love John Stuart Mill—is a Francophile, a one-woman man, he is sort of sentimental … Now, John Stuart Mill was all of those things, he really was, but those were the elements that I would pick out. Henry Finder would say that I draw myself more as John Stuart Mill than as myself, because in the more personal writing I am more equitable, careful, modest, more self-deprecating than I actually am. I am a much more irascible person in reality than the narrative voice in my work.

Z: It struck me that the persona of the narrator in most of your writings is this very poised, balanced, tolerant, self-erased person, and yet you are a Francophile. So how do you put up with French people [Gopnik laughs] who are notoriously intolerant, intense …

AG: …I do because they’re much more like I am that I am in my writing! I always tease my wife, Martha, because the world has this impression that I am this kind of wry, witty, laid-back observer of the world, and she knows me as the guy who is up at 3:30 in the morning cursing “Could you believe what this idiot wrote about…” [he impersonates an enraged insomniac].

Now, of course I don’t make up the stuff: it’s a role, it’s a persona, it’s a voice. Once I discovered that voice, I found that I could write in it.

The truth is, we all write the thing we are not. And we write the thing we are not in large part because it interests us. I would like to be the person whom I pretend to be in the pages of Paris to the Moon. I think every writer does that. It’s not an impersonation: this is what writing is. I’m sure that if we could go back and meet Montaigne, he would be much less engaging. Our impression would be, “Boy, he’s a very chilly, remote French aristocrat.” So, we all write things that we are not. And I do that, too.

But to the degree that one can judge oneself, the narrative voice in this particular book is probably closer to my own. It’s a little more energetic, a little more agitated.

Z: I thought that there was more passion in it than your previous memoirs.

AG: Yes, I think this guy is closer to the authentic one. But again, what’s the authentic one? That’s Montaigne’s subject, right? You know my favorite thing in Montaigne is that line that I am going to butcher because I can’t remember it in French: “We are double in ourselves, and we are the thing that we reject.” I think that’s profoundly true, and one of the things that I love about France, if I can broaden it that way, is that there’s a much greater tolerance for this kind of divided self.

It’s a funny example to take but a character like Romain Gary is a man of absolute contradictions [Gary is a French novelist famous for winning the Prix Goncourt twice, first under his name, then, at the end of his life, under the pseudonym of Emile Ajar]. He is taken, as a whole, in France much more easily than here. Here it would be a scandal on the front page of the Times. He would be in disgrace. But in France people said, “This is not a scandal. That’s human personality operating at a higher level.”

Z: You’ve been at the New Yorker for 25 years now. I remember reading that you started by sending “Talk of the Town” pieces every week.

AG: I would not send them. I would walk down 40 blocks. I had a basement room on 87th Street, which was the Brooklyn of 1980s. And I would walk 40 some blocks, and I would slip them under the door. I did that for a long, long time.

Z: Publishing in the New Yorker had always been your goal?

AG: It was my goal, and it had been for a long time. When I was about 7, I read James Thurber’s collected works and it had a huge effect on me. In a weird way, Thurber and Montaigne are very similar writers: very inward turning, neurotic, humorous. And I thought, “Oh, my goodness, I love this!” And I saw that it was dedicated to Harold Ross, the prestigious editor of the New Yorker. And I said to myself “This is what I want to do.” It was an ancient, antediluvian, foundational desire that I had. I just kept at it.

Z: Do you still have a goal as a writer, or a dream? In the book, you talk about the “hot ice cream” dream of Catalan pastry chef Albert Adrià (brother of chef Ferran Adrià) at el Bulli. For years this forerunner of molecular gastronomy has tried to make a hot ice cream, to no avail, but he keeps trying. What’s the equivalent of the hot ice cream dream for a writer?

Z: Do you still have a goal as a writer, or a dream? In the book, you talk about the “hot ice cream” dream of Catalan pastry chef Albert Adrià (brother of chef Ferran Adrià) at el Bulli. For years this forerunner of molecular gastronomy has tried to make a hot ice cream, to no avail, but he keeps trying. What’s the equivalent of the hot ice cream dream for a writer?

AG: I feel strongly, I feel deeply, that I have never really written a satisfying long narrative. I’ve gained some kind of “expertise,” in the craftsmanship sense of the word, in the 4,000-word essay. But I feel that I’ve never really written a satisfying long narrative. I have written two children’s books that were longer narratives, and though they are favorites of mine, it did not seem to connect with readers in the way other stuff had. If I had an ambition for the next decade, it would be to find ways of mastering – “mastering” is a bad word – of attempting longer narratives.

The other thing is what we’ve talked about before. Though I believe, I hope, that there is a broad range of emotions in my writing – from Greek melancholy, the elegiac, to humor, celebratory, and joy — I am also susceptible to lust and rage and anger, and I’ve never articulated those successfully in my writing. I recognize that if there is a hole in my work, it’s that there’s a whole aspect of human life that is no stranger to me that is not present. I don’t know if you can remedy that. It might be that it’s a defining thing, rather than a deficiency. We’re all good at something and not good at others.

Z: Do you think that you have acquired a voice that has a certain range and timber, and it is hard to stretch that voice to express anger and rage?

AG: Yes, it’s a voice that’s designed for singing ballads, and I don’t know if it can sing Webern for instance. But I’d like to try. That’s one thing that no writer really knows. When we are readers, we know: we like to read P.G. Wodehouse in his P.G. Wodehouse-way, and if P.G. Wodehouse tries to write tragedies, we’d be unhappy; when Woody Allen does serious work, we are less interested in it because it’s not his natural genius. At the same time I have great respect for Woody Allen for trying. In other words, we label that as “pretension” often, but often pretension is a nasty name for ambition, and ambitious artists tend to be more interesting in the long run than un-ambitious ones.

Z: So far you’ve been collecting essays by theme, but at the end of a career one could very well imagine that you would publish a book that would be even closer to the model of Montaigne’s Essays.

AG: I’d love to do that. Sort of a Big Book of Life. I would love at some point to collect all the best essays I wrote about sort of everything. I even have a title for it in mind: I want to call it Once A Philosopher, like Voltaire’s line, you know? You would have on the title page Once A Philosopher … then you open up the book and it says, “Twice A Pervert.” Because I do tend to write on things once. I’m very curious about them and I do them: dogs, or drawing, or whatever. Then I tend to leave them. That would be my Big Book of Life. It would be a non-thematic collection. Publishers tend to be not interested in non-thematic collections.

Z: So do you think that Montaigne would still have a public if he were published now? Would it be possible to publish The Essays as a form of book now?

AG: One of the things that happened is that the classic Montaigne essay has migrated to lots of other forms, and one of the forms it has migrated into is humor. People will read if it’s presented with humor. The best magazine pieces do that. My friend Louis Menand, who is a wonderful writer, is not really a book reviewer although he writes book reviews. That’s the form he has to write his essays in. But they are really all, in his own dry way, intensely personal essays about life. James Wood does that, too, in a different way. Essays now are always in disguise.

Z: If we come back to The Table Comes First, cooking, of course, is a great metaphor for writing. The metaphor runs discreetly through the book. You draw this funny analogy between shell beans and writing: “Like sentences, shell beans are a great deal more trouble to produce than anyone who is not producing them knows … And then even the best shell beans, cleaned and simmered, are like sentences in that nobody actually appreciates them as much as they deserve to be appreciated.” So I wanted to know what is the unit, or ingredient, you work on when you’re writing. Is it the sentence, the paragraph?

AG: It’s both, but primarily the sentence. To me a great piece is a sequence of memorable sentences. And I know that’s a sort of limiting thing. Maybe that’s why I can’t write effective narratives! But for me a wonderful epigrammatic sentence, an effective aphorism, that for me is like seeing a pregnant woman, it’s the perfectly shaped thing, pregnant sentences.

And then paragraph structure fascinates me, too. One of the things that drives me nuts when I’m reading even good academic writing is that nobody seems to have ever heard that sentence variation is a vital part of writing. These are people who are perfectly competent in every other ways, but every sentence is the same shape.

In the end though, you either can produce surprising, beautiful sentences or you can’t. Without that, all the erudition and intelligence in the world is not going to make any difference. For me, yes, a piece works when I can say that there are six good sentences in it. And a piece that does not have any good sentence is not worth reading. Now, having said that, of course I struggle over weeks and pull my hair to work on the structure, to make it logical, and move paragraphs around so that the sequence flows. All that stuff matters, too. But if I am answering honestly, yes, it’s the sentence that matters.

Z: You talk about the sounds of the words and how they influence how we taste food as well. You write, for instance, that “ice scream Sundae” tastes all the better because of the alliteration. Are you cooking as a writer? And as a writer do you write about food because of how it’s going to sound?

AG: In one way cooking for me is an escape from writing. No matter what you try, writing remains a frustrating thing. My wife is a moviemaker. Moviemakers are happy even when they’re making bad movies, because it’s a communal activity. Men are meant to work socially. Writing is completely isolating. It creates frustration, anger, resentment, and bad feelings. Cooking, even when you’re doing it alone, is inherently social because you’re doing it for someone else. So in one way cooking is a way to escape being trapped in your own head.

But in another way it’s certainly true that I am a creature of words and concepts. I’m aware that what I serve is probably written as much as it is cooked. I have an idea in my head about what I am ongoing to do. I’m a terribly ham-handed person. I don’t put a pretty plate on the table.

Z: But you put a pretty idea.

AG: Yes! And I have a good idea of what a pretty plate would be! Of course, cooking is in part wanting. It’s an act of imagination. And the food itself is often never as satisfying as your imagination of it, but you don’t stop. You don’t become frustrated because of this fact and say, “Oh well, I should do something else.” Instead, you’re driven to do the next thing, and this strikes me as being true of all our sensual appetites.

Z: When you’re an essay writer, everything is a potential topic. How do you stop your mind from constantly picking up topics to write about? And what is fair game?

AG: The sort of principle I use––this is going to make it sound much grander than it is––the way it works for me at least is this. Obviously, I do a fair amount of obligatory homework like anyone else. But for what I think of sort as my real work, it should be something that I have an obsessive relationship with. So I did a piece this summer about dogs. It began, as I explained in the piece, I got this dog. I hate dogs and I was falling in love with this little dog. I was telling my editor about it. Sort of every day I was reporting on it. He is this extremely insightful guy and noticed that in another piece I was working on about drawings, I mentioned a dog in a very positive light, so he asked me, “Have you totally lost your fear of dogs?” And I said, “Yes, I guess I have,” and he said, “Well you should write about it.” Because he could recognize that there was some bigger psychological truth about this.

But the obsession alone is not enough unless you can take what I always think of as a left turn into traffic––I say that as a non-driver. There must be some kind of intellectual obstacle that you have to get around. So in the dog piece for instance, I read this huge literature about the evolution of dogs then it started to get interesting. For years I had this very simple relationship with this tiny little creature that I had never expected to have in my life, and this is a wolf, and nobody knows why we all have them in our houses. It makes no sense! That’s kind of the left turn into traffic, when it takes on a larger meaning.

And then–you asked what was fair game–I realized that my kids are involved in this. When they were small I used to joke they chose to be born the children of a writer. But as they get older, their experience becomes their own. So, for instance, in that piece, my daughter had a much more interesting and complex relationship with the other women on the Havanese forum than I could quite write about. And in a weird way it was the best part of the story: how she impersonated a forty-something woman for all that time. I thought there must be a way that I can do that without betraying her confidence, a quieter way. So there’s a little turn in the piece where I sum this up in one line: “She would rather be a Havanese owner than have a Havanese.”

Cécile Alduy is Associate Professor of French Literature at Stanford University. The author of two books on Renaissance poetry, she has been published in the San Francisco Chronicle, Le Monde, and is a contributor to the Los Angeles Review of Books.