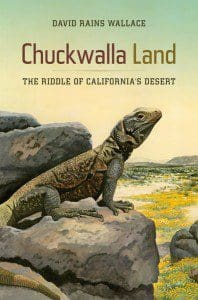

David Rains Wallace admits that for years he never really noticed California’s dry, empty spaces. It wasn’t until 1983, when writing about a Central Valley riparian woodland on the Kern River, that his attitude shifted from indifference to curiosity. Prior to that, whenever the award-winning nature writer found himself crossing California’s deserts he dismissed what he saw as an enormous vacant lot rather than a living landscape. In Chuckwalla Land: The Riddle of the California Desert (280 pages; UC Press), he explains this transformation.

David Rains Wallace admits that for years he never really noticed California’s dry, empty spaces. It wasn’t until 1983, when writing about a Central Valley riparian woodland on the Kern River, that his attitude shifted from indifference to curiosity. Prior to that, whenever the award-winning nature writer found himself crossing California’s deserts he dismissed what he saw as an enormous vacant lot rather than a living landscape. In Chuckwalla Land: The Riddle of the California Desert (280 pages; UC Press), he explains this transformation.

Wallace’s revamped attitude toward the desert and its denizens took shape during a serendipitous side trip on a two-lane road, often a gateway to consciousness-altering experiences. “The grotesquerie was unexpectedly enchanting. The weird formations seemed to act directly on my mind, to knead and stretch it, squeezing aside the worn furniture of normal perception. Two black army helicopters that thundered overhead failed to dispel the strangeness; in fact, they fit right in, more like mutant dragonflies from an atomic hinterland than enforcers of agroindustrial growth.”

He deftly guides the reader through a remarkable assortment of creation stories, mythology, 19th century Anglo American writing, and the differing theories of scientific research devoted to arid land studies. But during his research Wallace spotted a gap in the canon. He discovered there was no definitive explanation of how California’s desert plants and animals got into the desert, or how “the desert itself got into California. Nobody even knows how old it is.”

During Wallace’s erudite exploration of the “riddle” of the California desert, he strolls through a substantial sampling of primary and secondary source materials. But Wallace is not satisfied with merely recounting this illuminating and complex litany of interpretations. Instead, he takes the reader on an engrossing detour to the center of the intellectual battlefields of science and literature surrounding desert study. “This book won’t try to link California desert with conventional narratives. It will describe attempts to make such links, and the enigmas they have evoked.”

This result is a compelling compare-and-contrast narrative. Whether Wallace is examining competing scientific theories or the popular attitudes toward the desert throughout the ages, he simultaneously educates and delights.

Wallace explores the “heavy conceptual baggage” born out of opposing views of writers Mary Austin and John C. Van Dyke, or what the 1967 film Waterhole No. 3 reveals about us and our relationship to the desert. He introduces little known but important characters such as Edmund Jaeger, the mid-twentieth century writer and teacher whose work “influenced the creation of the first preserves — Death Valley National Monument and Anza-Borrego Desert State Park in 1933, Joshua Tree National Monument in 1936.”

Wallace devotes a good portion of the book to the careers of G. Ledyard Stebbins, a botanist and geneticist, Daniel Axelrod, a paleobotanist, and Jerzy Rzedowski, a major Mexican botanist, whose works contributed to the knowledge about the California desert.

Chuckwalla Land should finally retire the persistent myth of the desert as an environmental and intellectual wasteland.